Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

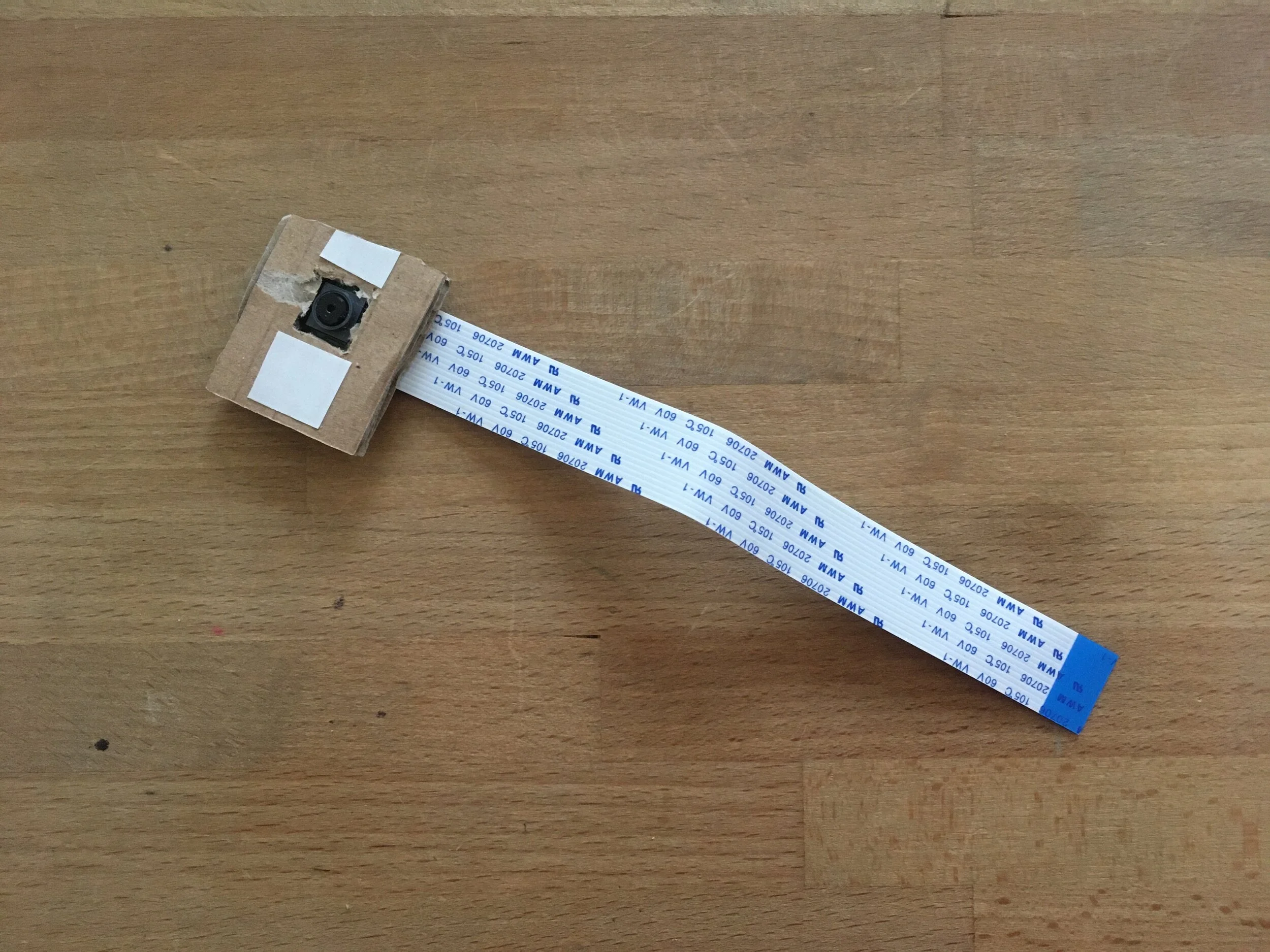

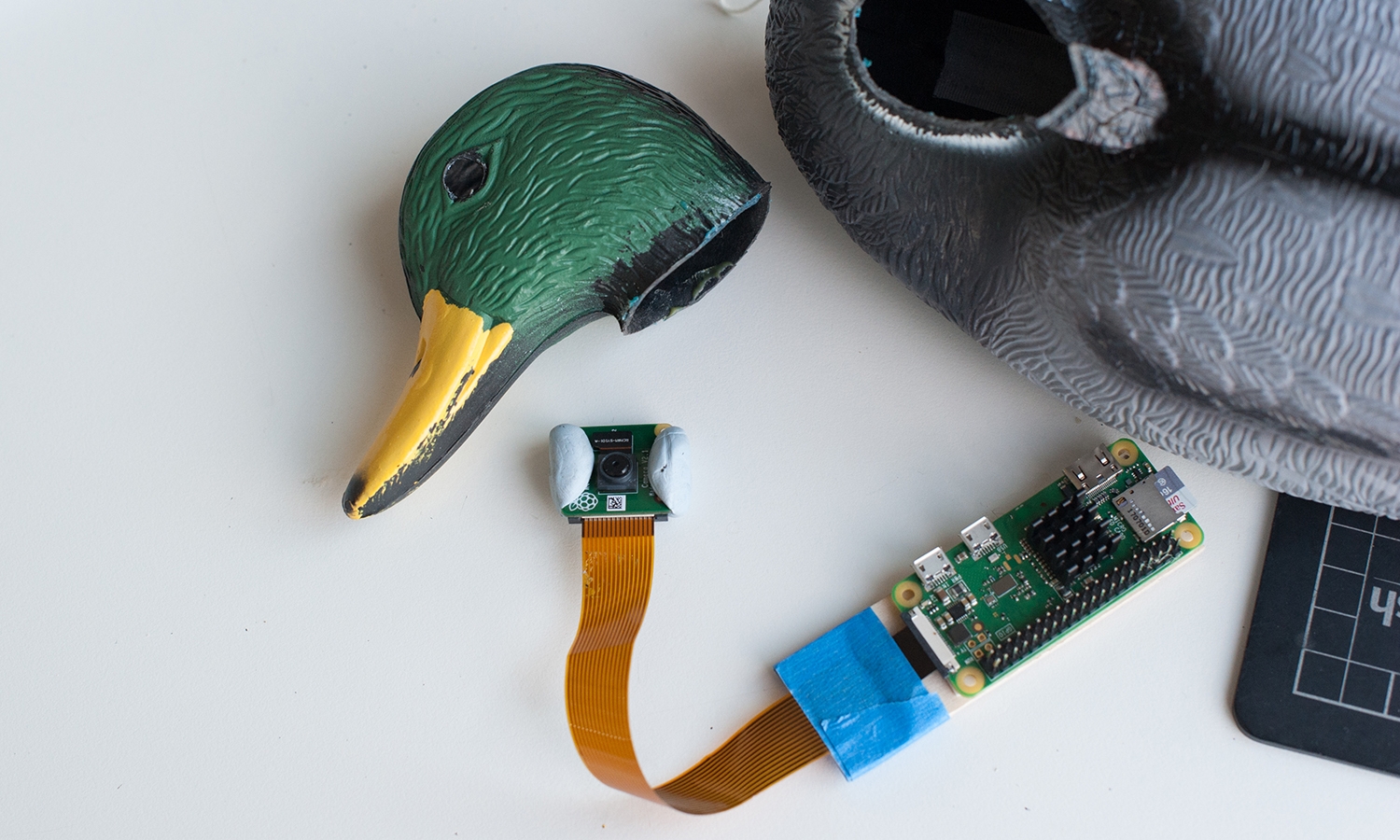

1. Cut a rectangular piece of cardboard slightly taller and quite a bit longer than the camera module. Cut a small camera lense sized square in the middle. Using double sided tape stick this to the front of the camera module. Then add more tape to the top of the cardboard, but leave it unpeeled for now.

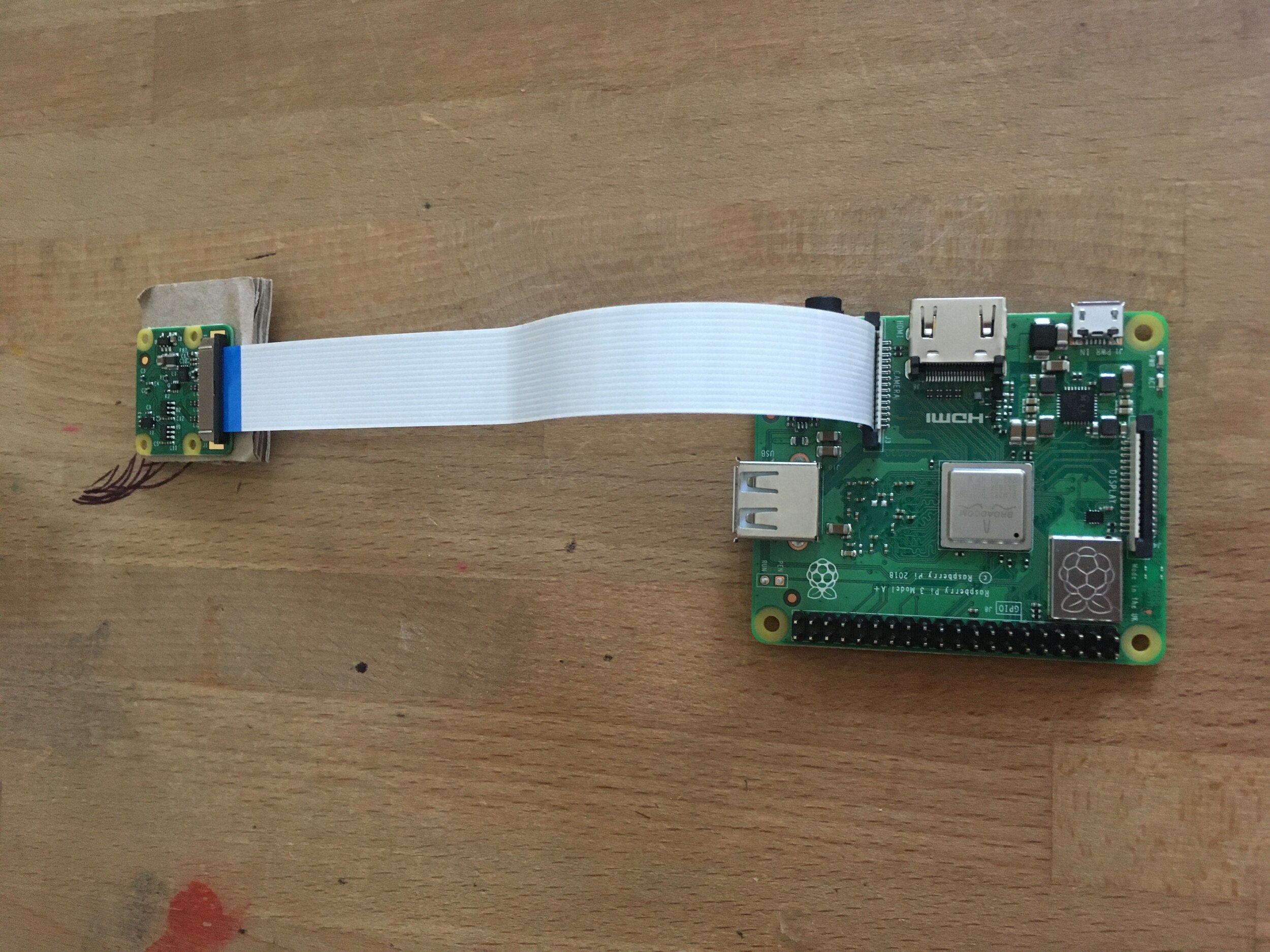

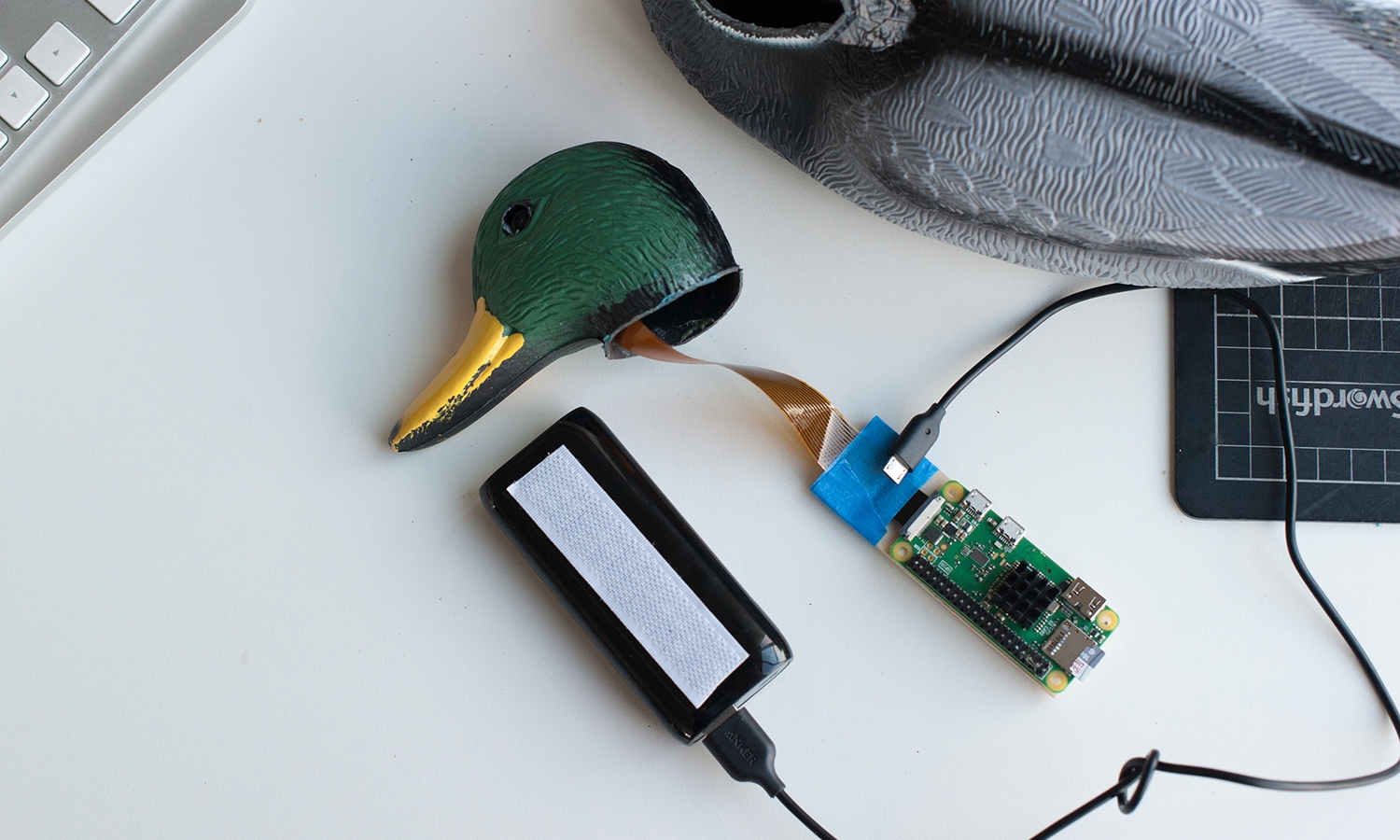

2. Connect the camera ribbon to the Raspberry Pi 3A+ via the narrow connector named ‘Camera’ and making sure it’s the correct way round as shown. Lock the Ribbon by pushing down on the black thingy.

3. Add the Heat Sink….

4. Insert the SD Card…

5. Plug in the USB Battery…

6. Secure the Camera Module to the inside of your food container using sticky tape. The Raspberry Pi and Battery can be left to to move freely within the container.